Manufacture of linen tablecloths & linen napkins

In the following we have compiled information about linen production for you. We try to give an overview of how linen was obtained in ancient times and how it was processed into linen tablecloths or linen napkins. The original centre of linen weaving in Germany was even here in Westphalia. The literature used for this article as well as general literature on the production of linen for linen tablecloths and linen napkins can be found at the end of this article. Most books can be consulted at „Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Münster“.

Flax becomes linen - linen becomes linen tablecloths and linen napkins

The cultivated plant flax has been widespread in the Mediterranean region since the 2nd millennium before Christ; flax from which linen tablecloths were also made in earlier times, came to Western Europe via Spain. The flax plant is one of the oldest plants cultivated by humans and still finds good growth conditions in Western Europe due to the moderately warm summer temperatures and the mild climate.  The flower is blue or white, its seeds are called linseed. They are the basis for our linen tablecloths and linen napkins. Linen (Greek: “linon”, Latin: “linum=flax”) is thus the name given to the flax fibre of the flax plant and thus to the fabric or cloth made from it, which is also called canvas. From the end of the 19th century onwards, linen was practically replaced by cotton in many areas. Today however, linen fabrics are once again gaining in importance and popularity as ecological natural fibres. Flax fibres are characterised by a high tensile strength, which is why they are also so well suited for textile production, especially of linen tablecloths. The fabric made from the flax plant is called linen or canvas. In earlier times linen was not only used for linen clothing or linen tablecloths, it was also used for the production of ship sails. For linen production, bast fibres are used, which are found in the bark tissue of the flax stalks. These approx. 30-90 cm long fibres were previously obtained in a very intensive and costly working process.

The flower is blue or white, its seeds are called linseed. They are the basis for our linen tablecloths and linen napkins. Linen (Greek: “linon”, Latin: “linum=flax”) is thus the name given to the flax fibre of the flax plant and thus to the fabric or cloth made from it, which is also called canvas. From the end of the 19th century onwards, linen was practically replaced by cotton in many areas. Today however, linen fabrics are once again gaining in importance and popularity as ecological natural fibres. Flax fibres are characterised by a high tensile strength, which is why they are also so well suited for textile production, especially of linen tablecloths. The fabric made from the flax plant is called linen or canvas. In earlier times linen was not only used for linen clothing or linen tablecloths, it was also used for the production of ship sails. For linen production, bast fibres are used, which are found in the bark tissue of the flax stalks. These approx. 30-90 cm long fibres were previously obtained in a very intensive and costly working process.

The sowing of linseed for the production of linen tablecloths

The flax, which will later be used for the production of linen tablecloths, is sown in northern Germany between the end of April and the beginning of May. Flax is an annual plant and must be sown anew every year. Linseed has been used as a seed since the 16th/17th century. After a few days, the seed rises and must be kept free of weeds. The flax weeding was in old times a laborious work, the proverb applied: “Bad flax does not give good yarn“. Approximately 100 days after sowing, usually at the end of July, the flax is ripe when the leaves turn yellow and the stalks turn yellowish, by which time the leaves in the lower third have already fallen off. Then the harvest of the flat can begin: Here the plants are not mown, but pulled out together with roots. In the old days, the individual bundles of flax were usually left to dry on the field for a few days before they were caught.

The production of flax fibres for linen tablecloths

In order to obtain the flax fibres, the seed capsules are first threshed out and then pressed into linseed oil in oil mills. The rippling can also take place after the rotting. The flax stems are then bundled again and placed in water. The moisture accelerates the rotting process and loosens the glue substance between the bast parts and the wood parts of the flax stalks. This process, which takes about 10-14 days, is called “roasting”, “retting” or “rotting”. The decomposition should be interrupted at the right time in order not to damage the fibres themselves. The flax stems are then spread out to dry and turned over at regular intervals. As soon as the stems become brittle, they are layered into bundles and, in good weather, the drying process continues in the sun. On large farms there are special flax dehydration ovens for this purpose.

The processing of the flat stems for line extraction

The production of linen for linen tablecloths continues after the roasting when the straw is broken: a flax stem lying on a wooden block is beaten with a rapping wood grooved on the underside in order to soften the woody stem components and remove the wooden parts from the flax stems. Larger quantities of flax could not be processed by hand, they were taken to a mill and beaten with horsepower.

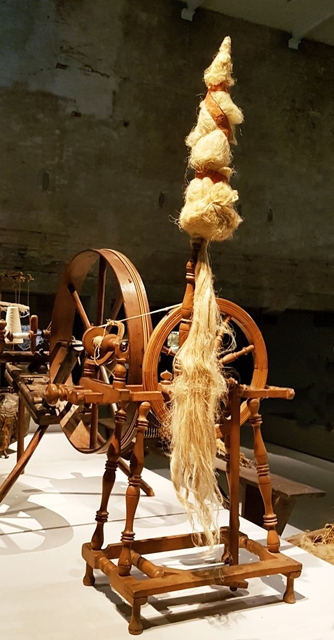

Spinning the canvas for linen tablecloths

In spinning, individual fibres are twisted together in such a way as to produce a fine thread that is as uniform as possible. This is particularly important for linen tablecloths and linen napkins. A spindle is used for spinning, an approximately 30 cm long wooden rod which twists the thread attached to it by turning it around its own axis. This ancient spinning process is already documented in Central Europe for the Neolithic Age (5000-2000 before Christus). It was not until the Middle Ages that the spinning process was mechanised in the form of a hand spinning wheel, with the spinning and winding of the yarn initially taking place one after the other. Only with the development of the wing spinning wheel around 1480 could the spinning and winding of the yarn be carried out in a single operation. The spun thread was wound on a reel. The reel resembles a spoke wheel, which carries small crosspieces instead of the tire, which take up the yarn. Since time immemorial, 60 threads have formed a bond, 20 bind a piece.

In spinning, individual fibres are twisted together in such a way as to produce a fine thread that is as uniform as possible. This is particularly important for linen tablecloths and linen napkins. A spindle is used for spinning, an approximately 30 cm long wooden rod which twists the thread attached to it by turning it around its own axis. This ancient spinning process is already documented in Central Europe for the Neolithic Age (5000-2000 before Christus). It was not until the Middle Ages that the spinning process was mechanised in the form of a hand spinning wheel, with the spinning and winding of the yarn initially taking place one after the other. Only with the development of the wing spinning wheel around 1480 could the spinning and winding of the yarn be carried out in a single operation. The spun thread was wound on a reel. The reel resembles a spoke wheel, which carries small crosspieces instead of the tire, which take up the yarn. Since time immemorial, 60 threads have formed a bond, 20 bind a piece.

Weaving linen tablecloths

When weaving canvas for linen tablecloths and linen napkins, the threads are crossed at right angles. First, the so-called warp threads are tensioned parallel to each other at equal intervals. The so-called weft threads are guided from the side alternately above and below the warp threads. This is also referred to as “yarn” or “weft”. The crossing of threads was already made much easier in ancient times by the loom: with the help of lifting beams and shafts, the warp threads were alternately raised and lowered. The weaving shuttle with the weft thread could be carried out so quickly. The weaver had to knock every thread firmly against the already woven linen after every throw. Linen can absorb well over 30 percent of air humidity and quickly exchange this humidity with the ambient air. In this way it has a cooling and warming effect at the same time and is an ideal fabric, especially for summer clothing. The linen fibre is extremely tear-resistant and inelastic, which is why it is also very susceptible to creasing. The high tensile strength makes the linen hard-wearing, but also susceptible to friction. It should therefore only be compressed in the laundry and not rubbed. Linen and linen tablecloths are strong and do not need to be re-strengthened. Linen is insensitive to many washing cycles and detergents and can be ironed very hot when still damp. However, linen and linen tablecloths should not be placed in the tumble dryer, as the dry heat causes lasting damage to the fabric.

Bleaching the canvas for linen tablecloths and linen napkins

The canvas was then boiled in a wood ash liquor or soap liquor, which was then washed out again in many laborious rinsing cycles. In this way, the lignin, the fibre glue, was removed from the canvas, but it was only by bleaching in the summer months from May to July that the canvas got its actual light colour. The farmers mostly bleached their linen themselves by spreading the lined canvas in strips on meadows and regularly sprinkling it with ditch water.  The screen was watered again and again and then bleached for hours in the sun. The chemical processes used in lawn bleaching are artificially imitated in modern detergents and bleaching agents. During the last drying process in the hot summer sunlight, the last folds were carefully removed from the canvas, the canvas was smoothed out and finally rolled up before it could be further processed, e. g. into linen tablecloths. The woven canvas itself varies greatly from very finely woven to the coarse bag canvas used for grain sacks in ancient times because of its high tear strength. A distinction is also made between bleached and unbleached canvas, smooth or patterned canvas and also coloured and uncoloured canvas. Most of the woven canvas was sold by many farmers, linen tablecloths were made from particularly high-quality, finely woven and lightly bleached cloth. Linen was sold by travelling merchants who bought the cloth in bales without cutting it up and marketed it nationwide. Some of the linen was kept by the farmers themselves, often given to the girls of the house later as a dowry on their marriage because it was so valuable. The linen and the linen tablecloths and other table linen were stored in old oak chests, which had to be airy and dry so that the linen would not become friable. An old saying paraphrases this: “Spun with diligence, bleached at the bronze, woven into linen, lies still here inside.”(from M. Barrel Von Flachs und Leinen in alter Zeit. Berichte und Bilder, Dokumente und Überlieferungen, Rheda-Wiedenbrück 1989, S. 91.) The linen treasure that was stored was considered a very valuable commodity: linen tablecloths with hemstitch, linen tablecloths with lace inserts, valuable embroidery on linen tablecloths and bedclothes, linen napkins with mitred corners, decorative cushions and parade cushions were kept here and were signs of the wealth and prosperity of a family. The individual laundry jams in the old chests and cupboards were traditionally held together with ribbons.

The screen was watered again and again and then bleached for hours in the sun. The chemical processes used in lawn bleaching are artificially imitated in modern detergents and bleaching agents. During the last drying process in the hot summer sunlight, the last folds were carefully removed from the canvas, the canvas was smoothed out and finally rolled up before it could be further processed, e. g. into linen tablecloths. The woven canvas itself varies greatly from very finely woven to the coarse bag canvas used for grain sacks in ancient times because of its high tear strength. A distinction is also made between bleached and unbleached canvas, smooth or patterned canvas and also coloured and uncoloured canvas. Most of the woven canvas was sold by many farmers, linen tablecloths were made from particularly high-quality, finely woven and lightly bleached cloth. Linen was sold by travelling merchants who bought the cloth in bales without cutting it up and marketed it nationwide. Some of the linen was kept by the farmers themselves, often given to the girls of the house later as a dowry on their marriage because it was so valuable. The linen and the linen tablecloths and other table linen were stored in old oak chests, which had to be airy and dry so that the linen would not become friable. An old saying paraphrases this: “Spun with diligence, bleached at the bronze, woven into linen, lies still here inside.”(from M. Barrel Von Flachs und Leinen in alter Zeit. Berichte und Bilder, Dokumente und Überlieferungen, Rheda-Wiedenbrück 1989, S. 91.) The linen treasure that was stored was considered a very valuable commodity: linen tablecloths with hemstitch, linen tablecloths with lace inserts, valuable embroidery on linen tablecloths and bedclothes, linen napkins with mitred corners, decorative cushions and parade cushions were kept here and were signs of the wealth and prosperity of a family. The individual laundry jams in the old chests and cupboards were traditionally held together with ribbons.

Literature used for this article:

- Fasse, Marianne, Rund um Flachs und Leinen, Sprichwörter und Redensarten, Volksglaube und Brauchtum, Gedichte, Lieder und Märchen aus der Spinnstube, Münster 2003.

- Fasse, Marianne, Von Flachs und Leinen in alter Zeit, Berichte und Bilder, Dokumente und Überlieferungen, Rheda-Wiedenbrück 1989.

- Schoneweg, Eduard, Das Leinengewerbe in der Grafschaft Ravensburg. Ein Beitrag zur niederdeutschen Volks- und Altertumskunde. Nach der Ausgabe von 1923 ergänzt um einen Beitrag von Heinz Potthoff, Das Ravensbergische Leinengewerbe im 17. Und 18. Jahrhundert und ein Verzeichnis der mundartlichen Fachausdrücke, herausgegeben von Ernst Helmut Segschneider, Osnabrück 1985.

- Diers, Hedwig, Die schönsten Leinen-Stickereien, Münster 1993.

Further references for linen production:

- Eduard Schoneweg, Das Leinengewerbe, ein Beitrag zur niederdeutschen Altertumskunde, Osnabrück 1985.

- Ottfried Dascher, Das Textilgewerbe in Hessen-Kassel vom 16. bis 19. Jahrhundert, Marburg 1968.

- Heinrich Hahn, Geschichte der Handweberei im Schlitzerland, Schlitz 1978.

- Will Erich Peuker, Die schlesischen Weber, Darmstadt 1971.

- Klaus Tidow, Die Leinenweber in und um Neumünster, Neumünster 1976.

- Rheinisches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde, 27. Band - 1987/88, Textilarbeit.

- Hans Michel, Die hausindustrielle Weberei Deutschlands, Entwicklung, Lage, Zukunft, Jena 1921.

Interesting links for linen production:

- Article Linen, in: Wikipedia. Die freie Enzyklopädie.

- Article Linen fibers, in: Wikipedia. Die freie Enzyklopädie.

- Article Extraction of the linen, in: leinen.biz

- Article Cultivation and harvest of flax, in: gesamtverband-leinen.de